The Feinstein International Center is a research and teaching center based at the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University. Now more than ever, their mission of promoting the use of evidence and learning in operational and policy responses to protect and strengthen the lives, livelihoods and dignity of people affected by or at risk of humanitarian crises.

Since 1997, the Center has broadened far beyond its initial remit of studying famine, and is now an inter-disciplinary research center that seeks to build the evidence base to support and build the resilience of populations at risk across a broad spectrum of geography and hazards. Their mandate also includes a call to train a new generation of humanitarian analysts, activists and aid workers in a rapidly changing field. The Center's research, teaching, and actions focus on people affected by conflict, disasters, economic crises, and serious crimes and violations. Work continues to emphasize on-the-ground research in crisis-affected locations, in collaboration with local researchers or organizations, and remains tied to global decision-making or resource allocation processes.

This year we also welcomed new leadership with the hiring of Gregory Gottlieb as the Director of the Center and the Irwin H. Rosenberg Professor in Nutrition and Human Security.

19

Active Projects9

Courses in Humanitarian Assistance18

Areas of study (see map below)42

Research partner organizations

Famine - An Unnatural Disaster

With an ever-increasing number of the world's population on the brink of famine, how can we prevent politics and conflict from getting in the way of nourishing people? For over 20 years, the faculty and researchers at the Feinstein International Center have dedicated themselves to answering this question. Although work at the Center has expanded greatly over the past two decades, the fundamental work of preventing and mitigating the damage from famine is unfortunately more relevant than ever.

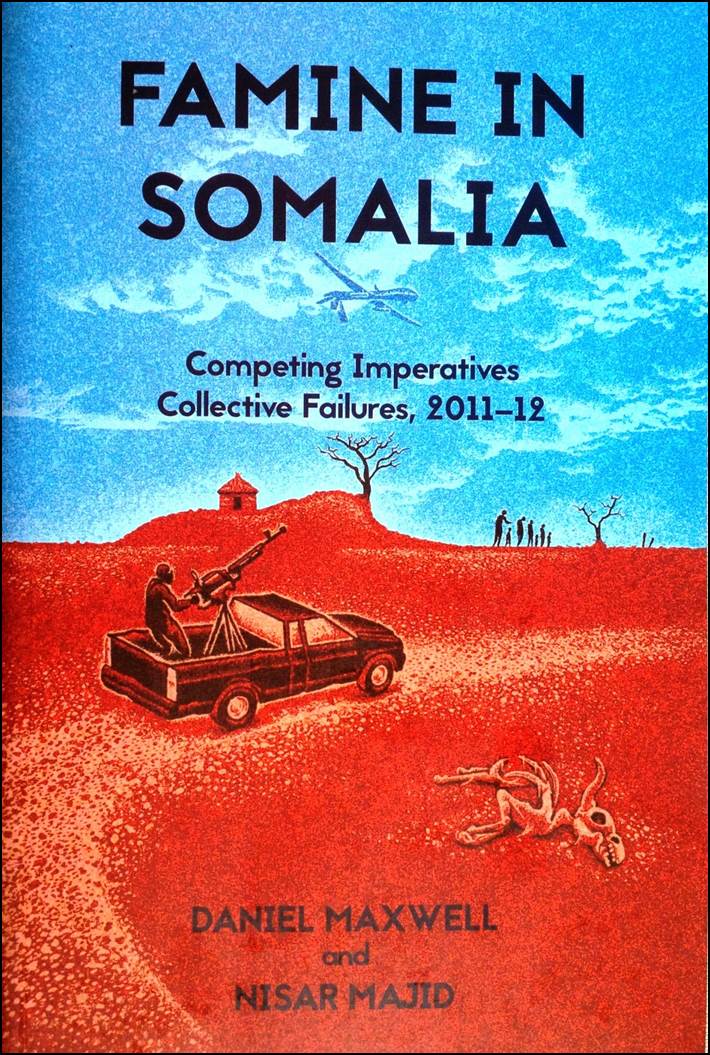

Professor Dan Maxwell's book, Famine in Somalia takes a critical look at how a conflict in Somalia turned into a humanitarian crisis where over 250,000 people died.

Associate Professor Jennifer Coates gives a high-level view of what a famine is.

A major famine struck Somalia in 2010-2011, and killed over a quarter of a million people. The Feinstein International Center was called upon to provide technical backstopping to UNICEF during the famine itself, and later Feinstein staff participated in evaluations of the response. This led to a major three year retrospective study of the famine, which considered the following: the reasons for the delayed international response, the engagement of non-Western humanitarian actors, the agency and actions of affected communities and groups in protecting their own livelihoods and lives.

The research resulted in the publication of a book by Daniel Maxwell and Nisar Majid in 2016 (Famine in Somalia: Competing Imperatives, Collective Failures, 2011-2012). Follow-up work has focused on interventions aimed at building resilience in the famine-affected areas, as an alternative to recurrent humanitarian aid. This includes defining and measuring resilience, and developing the means for real-time shock monitoring. Read an interview with Professor Daniel Maxwell about the famine and learn more about the book.

Hungry for Answers - Refugees and the Food System

What is the best way to get desperately needed food to people who have been forced to flee their homeland because of war, natural disaster or persecution? The traditional method of providing aid has been either distributing sacks of flour or rice off the back of trucks, or handing out packages of oil, pasta, lentils and other foods to families residing in camps.

But the strategies for delivering food aid have not kept up with the times, according to Karen Jacobsen, who directs the Refugees and Forced Migration Research Program at the Friedman School’s Feinstein International Center. Now Jacobsen, the Henry J. Leir Professor in Global Migration at the Fletcher School, is analyzing new methods for serving one of the world’s most vulnerable populations.

Syrian refugees use humanitarian aid vouchers to shop at a mall in Amman, Jordan. Photo: Muhammad Hamed/Reuters

What is the point of relying on a strategy of distributing food to refugees living in camps, Jacobsen asked during a recent interview, when most refugees do not live in camps at all? Of the 2.29 million Syrian refugees living in Turkey, for example, 90 percent live in residential communities, alongside people who are not refugees. For that reason, Jacobsen said, humanitarian organizations have begun turning away from shipping bags of commodities and instead are giving refugees the means to buy their own food—“especially in urban areas, and especially for Syrian refugees.” That often means vouchers that can be used at supermarkets or even cash wired directly to those in need.

In the end, solving the problem of feeding millions of refugees may mean reimagining humanitarian aid as something more holistic, that addresses not just hunger but the many interconnected struggles that go along with urban poverty. It’s a new way of thinking, and one that Jacobsen, Maxwell and their colleagues will be pushing the sometimes entrenched humanitarian industry to explore. Read the full story at Tufts Magazine.